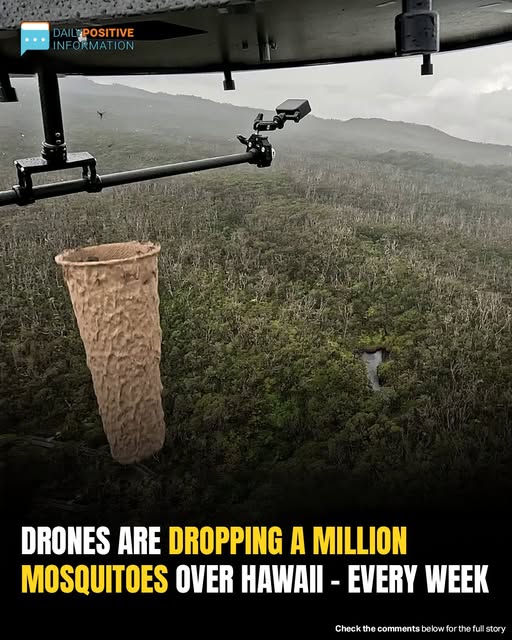

Dozens of biodegradable pods dropped from the sky over Hawaii’s woods in June. Each drone-delivered one has roughly 1,000 insects in it.

They were lab-raised male mosquitoes that were non-biting and carrying a common bacteria that causes the eggs of the males to mate with wild females and not develop. It is hoped that they would aid in the management of the invasive mosquito population throughout the archipelago, which is causing native bird populations, including the endangered Hawaiian honeycreepers, to decline.

A vital part of Hawaiian culture and an important pollinator and seed disperser, the birds are in terrible shape. Only 17 species of honeycreepers remain in Hawaii now, the majority of which are endangered, compared to the more than 50 species that were originally known to exist there.

Less than 100 yellow-green ʻakekeʻe are thought to survive, and last year the little grey bird known as the ‘akikiki became functionally extinct in the wild.

Although development and deforestation have had an effect, the “existential threat” is avian malaria, which is spread by mosquitoes, according to Dr. Chris Farmer, Hawaii program director for the American Bird Conservancy (ABC).

Although not indigenous to Hawaii, the insects were first documented there in 1826, most likely accidentally brought over by whaling ships. Farmer claims that because many local species, like honeycreepers, had resistance to the disease, “they caused waves of extinction.”

According to him, the remaining honeycreepers sought sanctuary higher up in the mountains of islands like Maui and Kauai since mosquitoes prefer the warmer tropical ecosystems found in the low elevations of Hawaii’s islands.

Now, this is changing. “With climate change, we are seeing warmer temperatures and we’re watching the mosquitoes move up the mountains,” he says. “(In places like Kauai) we’re watching the populations of birds there just completely plummet.”

“It’s a constant march of mosquitoes moving up as the temperatures allow them and the birds getting pushed further and further up until there’s no habitat left that they can survive in.”

“If we don’t break that cycle, we’re going to lose our honeycreepers,” he adds.

Searching for a solution

In order to keep mosquito populations under control and provide honeycreepers a lifeline, conservationists have been looking for a solution. However, managing mosquitoes at the landscape level is challenging, according to Farmer, who also notes that using pesticides, for example, might harm native insect populations that are essential to ecosystems, including fruit flies and damselflies.

Scientists have studied the issue for decades and have developed a number of remedies, such as the incompatible insect technique (IIT), because mosquitoes pose a serious threat to human health by spreading diseases like dengue fever, zika virus, and human malaria.

This entails releasing male mosquitoes carrying a strain of the naturally occurring bacteria Wolbachia, which, when they mate with wild females, results in non-viable eggs. This should eventually lead to a reduction in the natural population through repeated releases.

After determining that IIT had the best potential of success in Hawaii, ABC and Birds, Not Mosquitoes, a multi-agency partnership devoted to safeguarding Hawaiian honeycreepers, began looking into ways to apply the same strategy to mosquitoes that transmit avian malaria in 2016.

“The mosquito that transmits avian malaria is different from the one that transmits human malaria,” explains Farmer, so they began testing various strains of Wolbachia within the southern house mosquitoes found in Hawaii to determine which one was most effective.

The process took several years, due to “a combination of the science, community engagement and the regulatory process,” says Farmer, adding that, naturally, “whenever you say, ‘I want to release millions of mosquitoes in the forest,’ people have a lot of very legitimate questions.”

They began increasing production in 2022 and raised millions of mosquitoes in a California lab using the selected strain of Wolbachia. In the subsequent year, they began releasing the insects from helicopters in biodegradable pods in Maui’s honeycreeper habitats.

“We have a rough estimate for how many mosquitoes there are in the wild, and we try to release 10 times as many of these Wolbachia mosquitoes, so (that they) find these females and are able to mate with them, and then their eggs don’t hatch,” says Farmer.

“Right now, we’re releasing 500,000 mosquitoes a week on Maui and 500,000 mosquitoes a week on Kauai,” he adds, using both drones and helicopters.

Farmer claims that this is the first instance of IIT being utilised for conservation in the world. If it works, he believes it will inspire further applications. However, he cautions that although they felt comfortable employing the method in Hawaii because mosquitoes are an invasive species that have only existed for 200 years and thus do not significantly contribute to the ecosystem, the method may have unforeseen ecological consequences in other nations where they are native.

Buying time

The isolated, mountainous landscape of Hawaii, which is vulnerable to severe winds and erratic weather, has been one of the main obstacles to the insects’ release. According to Farmer, the program has had to rely primarily on helicopters for releases, but these are costly to operate and there aren’t many in the archipelago, and there are conflicting demands for safety, tourism, and firefighting. He says that weather has frequently forced last-minute mission cancellations.

Drones are useful in this situation. In June, they began successfully delivering mosquitoes via drone after months of testing the aerial vehicles in harsh environments, determining their range, and creating protected, temperature-controlled packages that can securely hold bugs and be attached to the body.

It is the “first known instance of specialized mosquito pods being dropped by drones,” says Adam Knox, project manager for ABC’s aerial deployment of mosquitoes. “We have more flexibility with deployment timing in areas that generally have very unpredictable weather and it’s safer because no humans need to ride in the aircraft to deploy the mosquitoes.”

It also “reduces costs, team flight times, emissions and noise, which in turn means cheaper, more sustainable deployments,” he adds.

The farmer anticipates that it will take a year or so to see the outcomes of the deployments and determine whether the IIT technique is effective. But he’s optimistic that it will help “buy time” for the birds to heal.

According to a recent research by the Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, if IIT mosquito control measures are effective, honeycreepers like the ʻakekeʻe can still be saved from extinction.

Christopher Kyriazis, postdoctoral researcher from San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and lead author of the report, told CNN that their modeling demonstrated the urgency of the situation: “If you wait even a couple years, the window narrows really quickly.”

While IIT is “ambitious” and has never been used on this scale for these sorts of conservation aims before, he believes “there is hope for the species, if it can be effective.”

Controlling mosquito populations could give honeycreepers more time to repopulate and increase their genetic variety, potentially leading to the development of their own resistance to avian malaria. According to Farmer, there are already indications that this is occurring with one species of honeycreeper on Hawaii Island, the ‘amakihi.

However, Kyriazis cautions that “even if a (protective) mutation did arise at this point, for it to be able to spread through the population fast enough to save it is very unlikely.”

Reintroducing captive populations of birds like the ‘akikiki,’ which is endangered in the wild but is being bred in bird conservation centres in Hawaii, might also be possible in a safer setting.

Being at the vanguard of this endeavour and witnessing the extinction of birds is “soul shattering,” according to Farmer. However, it also motivates him.

“We have the ability to save these species,” he says. “If we don’t save these birds in this decade, then they probably won’t be here for the future. And so the ability to make a difference in the world, make a difference in the future, motivates us all.”