The past often feels like a distant place, blurred by nostalgia and softened by time. But sometimes, a single image pulls us back with striking clarity—and demands a second look. One such photo from the 1975 Academy Awards is doing just that. At first glance, it radiates elegance: bright lights, glamorous gowns, polished tuxedos. But as it makes its rounds online once again, people are looking closer—and many are walking away with a bitter taste.

There’s something haunting about photos from the golden age of Hollywood, especially the 1970s. The stars seemed larger than life, yet still accessible. The Oscars weren’t just an award show—they were an experience, broadcast into living rooms around the world, shaping how generations viewed fame, beauty, and success. The 47th Academy Awards in 1975 captured all of that and more: glitz, history, tension, and raw emotion. But within that night lies one photo—just one—that continues to stir debate nearly 50 years later.

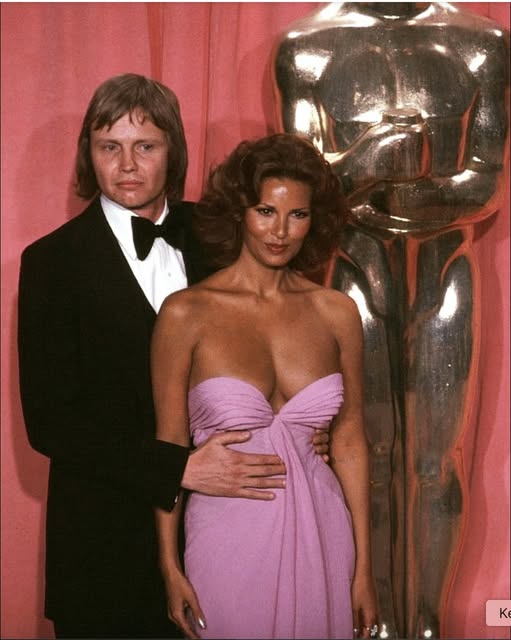

The photo in question features Jon Voight and Raquel Welch presenting the Oscar for Best Cinematography. Welch stands statuesque in a shimmering gown, Voight beside her in a crisp black tuxedo. On the surface, it’s the kind of glamorous snapshot that belongs in a museum. But viewers today are split: some see timeless elegance, others see discomfort hidden in plain sight. Voight’s body language has drawn criticism, with some saying he appears too close, too familiar. Welch’s expression, too subtle for the era but glaringly clear to modern audiences, suggests she may not have welcomed the contact. It’s a snapshot frozen in time, and like all relics, it invites both admiration and scrutiny.

But this wasn’t the only controversial moment from that evening.

Dustin Hoffman, nominated for his role in Lenny, had famously criticized the Academy Awards as artificial and shallow. He described the event as “grotesque” and “embarrassing”—a staged celebration of celebrity rather than artistry. Bob Hope, the ceremony’s emcee, couldn’t resist poking fun, suggesting that if Hoffman won, someone else would have to accept the award on his behalf—just like George C. Scott had done years earlier when he famously declined his own Oscar.

Hoffman didn’t win that night, but the jabs kept coming. Frank Sinatra, co-hosting the ceremony, took aim at Hoffman and other critics, delivering remarks that were awkward at best and offensive at worst. Slurring his words and fumbling lines, Sinatra’s digs at fellow Italian-Americans drew boos from the crowd, and critics like Roger Ebert later called the performance “an embarrassing spectacle.”

Then there was Bert Schneider’s acceptance speech. When Hearts and Minds won Best Documentary, the director used his moment not to thank his team or praise the Academy, but to make a political statement. He read a telegram from a Viet Cong ambassador, thanking the American anti-war movement. The message—delivered just as the Vietnam War was drawing to a painful close—sent shockwaves through the auditorium. Bob Hope was reportedly furious. Within the hour, a damage-control statement condemning Schneider’s remarks was drafted and read aloud by Sinatra on-air.

That response didn’t sit well with everyone. Actor Warren Beatty, seated nearby, reportedly muttered, “Thanks, Frank, you old Republican,” into a hot mic. Shirley MacLaine added, “You didn’t ask me!” The friction between the old Hollywood establishment and the newer, more outspoken generation was on full display—broadcast for millions to witness.

Another moment of quiet controversy came when Ingrid Bergman accepted the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. Her win, for Murder on the Orient Express, was met with warm applause. But when she stood at the podium, Bergman, with grace and humility, admitted she didn’t feel she deserved it. She believed Valentina Cortese should have won and said so publicly. Many believed Bergman’s win was less about performance and more about Hollywood’s long-overdue attempt at redemption—making up for how it had cast her out decades earlier over a public affair.

Looking back, the 1975 Oscars were not the elegant, apolitical affair some remember. They were messy, emotional, charged with politics and personality. And that’s exactly why they remain so relevant.

The resurfaced photo of Welch and Voight is just a symbol—a flashpoint in the larger conversation about how we view the past through the lens of the present. It challenges the myth of “simpler times” and forces us to ask: were things really better, or did we just not talk about the uncomfortable parts?

For some, the image is a cherished memory of Hollywood glamor. For others, it’s a stark reminder that appearances often masked discomfort. Perhaps both are true. Perhaps that’s what gives it power.

History is rarely black and white, especially in a town that runs on illusion. But when a single photo can spark this much conversation, it’s worth more than nostalgia. It becomes a mirror—not just of who we were, but who we are now, and what we’ve learned along the way.

So take a closer look. Not just at the photo—but at what it reveals. The past may be behind us, but the conversation is still very much alive.